7.1 The key actions in the Do part of the framework are Profiling your organisations health and safety risks; Organising for health and safety and; Implementing your plan (refer to HSE publication HSG65 for general guidance).

Profiling your organisation’s health and safety risk

7.2 Work, including safety critical work, can be undertaken on a transport system at any time during the day or night, sometimes in difficult circumstances and at times with demanding work schedules. The potential for fatigue should therefore be foreseeable in such circumstances. If adequate measures are not taken to control any resulting fatigue, it can in turn lead to human error and give rise to significant risks to people on the transport system. As described in Planning for implementation (paragraphs 6.22 to 6.41), dutyholders must carry out a risk assessment to determine the greatest fatigue risks in their organisation, set their priorities and identify appropriate measures to control those risks. This will involve identifying both the staff at risk of fatigue and the risks that the staff and organisation face.

Identify the staff at risk of fatigue

7.3 Dutyholders should identify workers at risk of fatigue. For example, those working shifts, overtime, and those carrying out safety-critical work. In particular, controllers of safety critical work need to identify those people carrying out safety critical work, since if these staff become fatigued there are likely to be adverse effects on the safety of people on the transport system.

7.4 Contractors should be considered as well as employees. For example, arrangements for awarding contracts and subsequent compliance monitoring arrangements should ensure, so far as reasonably practicable, there are no financial incentives for contractors to operate with high or unmanaged levels of fatigue. Organisations responsible for awarding contracts, where contractor fatigue could increase risk, should make their expectations on fatigue management arrangements clear to contractors during the bidding process. These expectations should be so far as is reasonably practicable embedded in contractual requirements.

7.5 In circumstances where the consequences of contractor fatigue are high, and to fulfil their duties under ROGS 2006, infrastructure managers and those otherwise in control of premises may legitimately require dutyholders accessing their infrastructure / premises to adhere to fatigue controls e.g. regarding staff travel and lodgings. In a commercially competitive market, less responsible companies may try to secure work by cutting costs without properly considering fatigue risks. They may try to use fewer staff, working longer hours or travelling long distances before and after work, thereby increasing fatigue risks. Work should only be awarded where sufficient allowance has been made for staff travel and accommodation in the costs.

7.6 Clarity in such expectations helps create a ‘level playing field’ for contractors by reducing opportunities for under-cutting, while allowing more realistic resource planning and costing. Contractors should in turn co-operate and comply with these expectations.

7.7 It is recommended that employers require employees to declare any second jobs which could affect fatigue risks. Employers should assess the potential impact on their own operation which the likely increase in fatigue from a second job would bring, e.g. due to the reduced opportunity for sleep. A smart-card system could help reduce ‘second job’ risks from staff working for more than one rail employer.

7.8 The safe and efficient operation of the railway depends not only on good co-operation within organisations, but also on the co-ordination and co-operation of other parties – for instance the many employers and their workforces who work together to provide and maintain rail infrastructure under the oversight of the infrastructure controller. So, in addition to co-operation within each organisation, companies should consider what arrangements they may need to co-operate with other dutyholders on controlling fatigue risks (Regulation 11 of the Management of Health and Safety at Work Regulations 1999, and Regulations 22 and 26 of ROGS Regulations 2006).

Identify the risks faced by staff and the organisation

7.9 A number of factors may affect the onset of fatigue, including the nature of the work itself. Tasks that require sustained vigilance, or where the employee may have low levels of workload, may be more susceptible to fatigue. For example, driving the same route a number of times in the same shift can impact on fatigue. The working environment (including low lighting levels, high temperature, and quiet conditions) may also increase fatigue and feelings of drowsiness, particularly for sedentary tasks. In some roles, for instance track maintenance work, the amount of heavy physical work can increase fatigue.

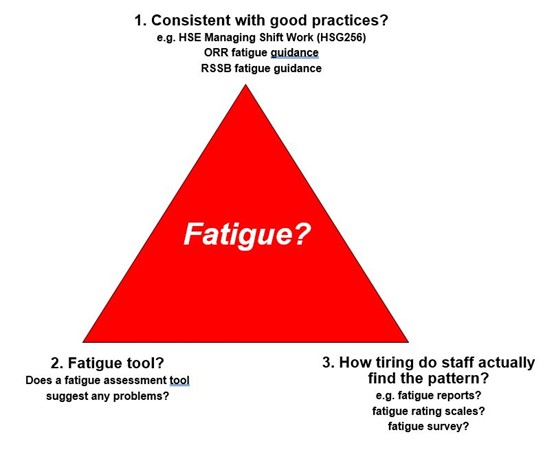

7.10 The design of working patterns or rosters is a significant contributor to the risk of fatigue. Dutyholders should take steps, so far as reasonably practicable, to manage the risk of fatigue from the design of working patterns. A three-part approach to managing the fatigue risk from working patterns, consulting with staff at appropriate stages, can be summarised as follows:

- design the work pattern, maximising good fatigue management practices

- assess likely fatigue risks from the resulting work pattern, using a fatigue assessment tool

- ask staff whether the working pattern is controlling fatigue, identifying any particular features which may need further improvement

7.11 A three-part approach is represented and described in Figure 7.1 below.

Figure 7.1 Triangulation approach to managing the fatigue risk from working patterns

Source: ORR’s superseded (2012) Managing Rail Staff Fatigue

1. Design the work pattern, maximising good fatigue management practices

7.12 Numerical limits on hours worked can help managers decide day to day what may or may not be acceptable. However, taken in isolation, a set of simplistic limits on work and rest hours cannot account for the impact on fatigue of operational factors such as differences in workload, working conditions and personal factors (age, health, medication, domestic and social activities) (Fourie and others, 2010a). The emphasis should always be on reducing risks from fatigue so far as reasonably practicable (involving judgements on risks and costs) rather than ‘working up to’ any particular limit. For these reasons, dutyholders need to set up and operate more wide-ranging fatigue risk management systems.

7.13 In recent years rail employers have often placed too much reliance on ‘Hidden limits’ incorporated into the former railway group standard GH/RT4004 (withdrawn 2007) and many company standards written following the 1988 Clapham accident. It is important to recognise that these limits were based on what was thought to be operationally achievable at the time, rather than on sound fatigue management science. These limits often became norms that companies routinely planned for and ’worked up to’, even though less fatiguing work patterns were available. Knowledge of fatigue has improved to recognise that some working patterns can give rise to significant fatigue even though they comply with the ‘Hidden limits’. Employers should devise their own arrangements for managing fatigue that include appropriate numerical limits. Guidance for designing work patterns is set out in ‘Implementing your plan’ (paragraphs 7.20 to 7.110).

2. Assess likely fatigue risks from the resulting work pattern, using a fatigue assessment tool

7.14 Draft working patterns incorporating, so far as reasonably practicable, good fatigue management principles, should include an assessment of the proposed pattern using a fatigue assessment tool to check whether the pattern would adequately control fatigue, and whether there are any opportunities for further reducing fatigue risks. This approach can give a more rounded assessment of the likely levels of fatigue from proposed working patterns, provided the assumptions and limitations of the tool are understood. ORR does not compel, endorse, or advocate the use of any one tool over another – all have their benefits and limitations, and it is for each organisation to decide which tool(s) best suits their requirements. The benefits and limitations of fatigue assessment tools are outlined in Appendix D.

7.15 Planned work patterns may vary when workers are on-call or for unplanned overtime e.g. worker shortages or sickness. Actual rather than planned working patterns should be assessed and managed to minimise the risks from fatigue. Proposed changes to planned work patterns should, wherever possible, be risk assessed before work commences to check whether good fatigue management practices have adequately been considered (see paragraphs 7.20 to 7.92 in Implementing your plan, including the summary in 7.92). Short-notice changes should be avoided so far as is reasonably practicable. Software packages are now available to help dutyholders estimate the likely fatigue risks from changes to planned rosters, provided their limitations are appreciated (see Appendix D on fatigue risk assessment tools).

3. Ask staff whether the working pattern is controlling fatigue, any particular features which may need further improvement

7.16 Whatever limits are used, they should not be used in isolation and from the outset should be complemented by building-in good fatigue management principles (see Designing working patterns (paragraphs 7.20 to 7.92 in ‘Implementing your plan’), and by consulting and seeking feedback from staff on how tiring they find the working patterns in practice.

7.17 Even if working patterns are designed according to good practice principles, with a fatigue risk assessment tool suggesting fatigue levels are unlikely to be a concern, and staff agreeing to the pattern, the working pattern can be fatiguing. General principles and fatigue assessment tools are not perfect – it is important to carry out a ‘reality check’ by seeking staff feedback on whether the pattern is adequately controlling fatigue in practice. Soon after the introduction of a work pattern, employers should ask staff directly how tiring they find it in reality. This can be done either directly or through trade union / staff safety representatives.

7.18 Further information on obtaining staff feedback can be found in Appendix C Fatigue reporting.

Organising for health and safety

7.19 ’Determining your policy’ outlined some possible benefits of creating a joint management / staff fatigue group to oversee fatigue control systems. In smaller organisations a single joint fatigue risk action group may provide a suitable forum for progressing fatigue management. Larger organisations may wish to assign strategic functions to a high-level Fatigue Risk Management Steering Group, and assign more routine, day-to-day implementation, and practical fatigue advice to a working level Fatigue Safety Action Group. It may well be appropriate for an existing joint management / staff group with a wider safety remit to take on board the fatigue functions suggested here, there is no ‘one-size-fits-all’. Whatever their name or constitution, such joint groups can play a key role in overseeing the practical development of fatigue controls and ensuring they are workable and effective. Some possible areas of activity for such joint fatigue groups include:

- direction on high level, strategic fatigue issues such as:

- overseeing collection of management information relevant to fatigue

- advising on fatigue aspects of staff terms and conditions, pay structures

- developing fatigue standards, procedures and other documentation

- advising on fatigue aspects of any organisational changes

- fatigue aspects of resource allocation (staffing levels etc.)

- procedures for managing overtime and on-call work

- establishing triggers for action on fatigue

- proposing, overseeing, and monitoring fatigue reduction strategies and plans

- making reasonable efforts to incorporate good fatigue management practices from comparable organisations

- more routine, day-to-day input on:

- helping managers and roster clerks devise fatigue-friendly working patterns and rosters

- helping managers with fatigue risk assessment including the use of any fatigue assessment tools

- monitoring fatigue information to identify trends, including comparisons of planned versus actual working patterns

- collecting data on any problematic shifts / rosters / diagrams etc.

- fatigue problem solving

- investigating exceedances of company fatigue limits, deviations from expected fatigue controls and incidents where fatigue may have contributed

- staff fatigue surveys and trends

- sickness absence trends and fatigue

- devising and delivering fatigue education and training programmes

- keeping senior management informed on progress with fatigue controls

- keeping staff, employee representatives and trade unions informed on progress with fatigue controls

Implementing your plan

Designing your work patterns

7.20 Dutyholders should identify, set and adhere to appropriate standards for working hours and working patterns, observing any relevant working time limits that apply.

7.21 The standards and limits set should take into account recognised national industry good practice guidance applying to railways and other guided transport systems designed to minimise features of working patterns known to contribute to fatigue.

7.22 They should take account of guidance in (for instance):

- HSE booklet HSG256 ‘Managing Shift Work’

- this ORR guidance (specific information on good practice working patterns can be found in paragraphs 7.28 to 7.92 including the summary in 7.92)

- ORR’s Fatigue Factors – good practice guidance – included in the appropriate sections below and in the summary in 7.92. More information can be found on ORR’s website (see further information)

- any role-specific fatigue guidance (for example RSSB, 2015 Research Report T059 for passenger train drivers, or RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 for freight train drivers and contract track workers)

7.23 To control the risks from fatigue, working patterns can be designed to:

- minimise the build-up of fatigue by restricting the number of consecutive night or early-morning shifts

- allow fatigue to dissipate by ensuring adequate rest between shifts and between blocks of shifts

- minimise sleep disturbance

7.24 Limits for hours worked and working patterns for safety critical workers are generally appropriate for:

- the maximum length of any work shift or period of duty

- the minimum rest interval between any periods of duty

- the maximum number of hours to be worked in any seven-day period

- the minimum frequency of rest days

- the maximum number of consecutive day shifts

- the maximum number of consecutive night shifts and early-morning shifts

- the maximum period of time between breaks, including breaks for meals

7.25 The standards and limits that the dutyholder sets should, so far as is reasonably practicable, take into account foreseeable causes of fatigue, including:

- job design

- the workload (physical and mental) and the working environment

- the shift system in operation

- shift exchange

- control of overtime

- on-call working

- the frequency of breaks

- recovery time during periods of duty

- the nature and duration of any time spent travelling either commuting or travelling to site

7.26 Dutyholders should consider these questions when designing work patterns:

- Overall, is the proposed working time pattern likely to increase the risk of accidents arising from fatigue?

- Does the proposed working time pattern have any particular feature that could give rise to fatigue risks?

7.27 To answer these questions, there are six aspects of the working pattern that are relevant to the question of fatigue, and they should be considered so far as is reasonably practicable. These aspects and the corresponding ORR guidance, based on good practice, are described below. Definitions of the various shifts and other relevant terminology can be found in Appendix E.

Shift length factors

7.28 Shift duration is a key factor influencing fatigue. Long shifts have been linked with an increased risk of accidents; therefore, companies should understand their working time risk profile when examining, assessing, and establishing shift patterns. This guidance also applies to split shifts as per the Definitions section.

7.29 Limit shift durations to 12 hours.

7.30 There is evidence that human performance deteriorates significantly when people have been at work for more than 12 hours. Staff who regularly work 12 hours or more per day were found, in a large US study (Dembe and others, 2005), to have a 37% higher injury rate compared to other staff. In a review of the relative risk of accidents or injuries, the risk of an incident was shown to increase with increasing shift length over eight hours, with 12-hour shifts showing a 27% increase relative to eight-hour shifts (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 p29, Folkard and others, 2006). Hence, there is a strong case for limiting shift duration to 12 hours, with further restrictions on duties, such as nights and early starts, that impinge significantly on the normal hours of sleep. RSSB proposes good practice for day shifts to be a maximum of 12 hours (RSSB, 2005 Research Report T059). A 12h day shift can be considered acceptable if other factors contributing to fatigue are correctly identified and mitigated, and if they are balanced by sufficient time off for recovery.

7.31 Limit shift duration to 8-10 hours especially for early and night shifts.

7.32 As described above, the risk of incidents increases with increasing shift lengths of over eight hours. 10-hour shifts were associated with a 13% increased risk relative to eight-hour shifts (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 p29, Folkard and others, 2006). Studies in the Australian rail industry have shown exponential safety declines with time on shift, with roughly double the likelihood of accident or injury after 10 hours relative to the first 8 hours (Dorrian and others, 2011).

7.33 While it may be acceptable to work a 12-hour day shift, lower limits such as 10 hours should be considered where night shifts or early morning start times are planned (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 44) so far as is reasonably practicable, and RSSB proposes good practice for early and night shifts to be a maximum of 10 hours (RSSB, 2005 Research Report T059).

7.34 Limit shift duration to 8 hours for early shifts starting before 05:00.

7.35 The interaction between shift start time, and time of day of the shift, has a strong influence on levels of fatigue (RSSB, 2012). RSSB proposes good practice for shift duration for early shifts starting before 0500 to be a maximum of 8 hours (RSSB, 2005, Research Report T059).

7.36 Other factors for consideration:

- Dutyholders should consider whether any shift (including overtime) could exceed 12 hours in length, and consider the risks involved in activities (whether at work or, for instance travelling home) that workers could be carrying out after the twelfth hour for example, suitable assessment and consideration should be given to any safety critical duties undertaken after the twelfth hour.

- Below 12 hours, the extent to which fatigue occurs may depend on other aspects of the working time pattern, such as the adequacy of breaks taken during the shift and the length of interval since the previous duty (as well as other factors such as the nature of the work, the working environment, individual variables and sleep history).

- Even shifts of eight hours or less can be fatiguing if the work is very intense, demands continuous concentration, there are inadequate breaks, or is very monotonous.

- It is important to recognise that controlling the time actually ‘at work’ may not properly manage work-related fatigue if travel times to, and/or from, the place of work to home, or lodgings, are significant. Some organisations, therefore, place limits on maximum ‘door-to-door’ times between leaving and returning to the home / lodgings. This more integrated approach has the added benefit of helping to control fatigue risks arising from travel to or from the workplace, including work-related road risks. See Appendix A on travel time for more information.

7.37 ORR Fatigue Factors for shift lengths:

Intervals between duties

7.38 The daily rest interval for safety critical workers needs to be risk assessed to enable them to return to work rested after a full rest period.

7.39 Provide a minimum rest period of 12 hours between consecutive shifts.

7.40 Studies suggest that the average amount of sleep required per 24 hours is 8.2 hours (Van Dongen and others, 2003). Where sleep is restricted to seven hours or less, there are cumulative effects on cognitive performance over successive days (Belenky and others, 2003; Van Dongen and others, 2003). In order to give opportunity for sufficient sleep, it is proposed that a minimum rest period of 12 hours between consecutive shifts is provided (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 45).

7.41 Provide a minimum rest period of 14 hours between consecutive night shifts.

7.42 For those working early starts, late finishes or night shifts, obtaining sufficient sleep may be more difficult and unless properly managed, staff may get well under eight hours sleep. In order to give opportunity for sufficient sleep between consecutive night shifts, it is proposed that a minimum rest period of 14 hours is provided (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 45).

7.43 Other factors for consideration:

- Some shift patterns provide a rest interval of only eight hours. This will not be adequate to obtain sufficient sleep (see paragraph 7.39), and patterns involving such short rest intervals should be revised as soon as is reasonably practicable. Until shift patterns are revised, other rest intervals within the shift pattern should be assessed for suitability.

- Long travel times to and from work can reduce the opportunity for required daily rest periods and so increase the risk of fatigue. There is evidence that time spent travelling to and from work does not provide rest in the same way as time spent at home. Therefore, travel time should be monitored and taken into account when considering changes to working time patterns, particularly for a group of safety critical workers with long travelling times. See Appendix A on Travel Time for more information.

- Providing temporary accommodation near to the workplace for overnight stays can help workers obtain the maximum sleep in the time available which may reduce the likelihood of fatigue.

7.44 ORR Fatigue Factors for intervals between duties:

Recovery time, i.e. rest days between successive shifts

7.45 Rest days allow the ‘cumulative fatigue’ which accumulates over successive shifts worked to dissipate.

7.46 The maximum number of consecutive day (including mixed patterns) shifts before a rest day should be seven.

7.47 There is clear evidence regarding the value of rest days in enabling workers to ‘recharge their batteries’ and to maintain their work performance (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699).

7.48 The maximum number of consecutive early shifts before a rest day should be five.

7.49 Early morning shift workers have to wake up very early and can have a reduced length of sleep, leading to a progressive build-up of fatigue over successive early starts. Staff may need longer to recover from a very early shift than a day shift (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 15).

7.50 The maximum number of consecutive night shifts before a rest day should be three.

7.51 The risk of accidents and injuries has been found to increase over spans of four consecutive night shifts (Folkard and Akerstedt, 2004). Some studies also indicate that performance errors increase, and alertness decreases over four consecutive night shifts (Walsh and others, 2004).

7.52 Staff may need longer to recover properly from a night shift than a day shift (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 15). Workers may have difficulty in adjusting to varying sleep patterns, or to daytime sleep; this is an effect of the internal ‘body clock’ (circadian rhythm) regulating sleep and wakefulness, which corresponds to the natural cycle of night and day. It may also be difficult to find the right conditions at home for daytime sleep. As a result, there may be a reduction in the quantity and quality of sleep, and the effects can build up over a period. On average, a person may lose two hours sleep for each night shift worked.

7.53 Consider shortening the first night shift in a series of night shifts or implementing other risk controls.

7.54 Some individuals report that over successive night shifts they find less difficulty concentrating and find sleep between shifts progressively easier, finding the first in a series of night shifts to be particularly fatiguing (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 pages 31, 34, 37). It may be that staff changing from a ‘daytime awake / night-time asleep’ pattern feel less fatigued on their second- and third-night shifts than their first night shift, as their ‘body clock’ (circadian rhythm) adjusts. However, this is probably countered by a steady accumulation in ‘sleep debt’ with each night worked due to generally shorter, poorer quality daytime sleep.

7.55 It is unlikely that individuals will adapt fully to night shifts – a study found that less than 3% of permanent night workers adapted completely (Folkard 2008, and RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 37).

7.56 The resulting fatigue that safety critical workers may experience is likely to be most noticeable on the night or early-morning shift, and to be more marked the more monotonous or repetitive the task. Individuals vary in their ability to cope with successive night shifts. While some people prefer to work more consecutive shifts in order to take a block of days off afterwards, this needs to be balanced with the risk of higher levels of fatigue from the greater number of shifts worked.

7.57 Employers should assess the relative pros and cons of such trade-offs and make a judgement on the best overall solution, documenting their reasoning.

7.58 Allow two rest days before an early start which follows a night shift.

7.59 An RSSB study found that most drivers work for five or six days before a break of at least one day, although the maximum number of days worked consecutively was nine. One quarter of drivers worked on their scheduled rest day between two and three times each month. This loss of rest days increases risk associated with working on consecutive days. This is particularly problematic when returning to early shifts after late or night shifts (RSSB, 2005 Research Report T059).

7.60 Allow one rest day before an early shift which follows a late shift.

7.61 As described above, this is also problematic when returning to early shifts after a late shift (RSSB, 2005 Research Report T059).

7.62 Minimise rest day working.

7.63 Rest day working should be kept to a minimum to ensure that planned recovery time achieves its objective and staff return to work refreshed.

7.64 Other factors for consideration:

- The planning of rest day arrangements for safety critical workers needs to take account of the length of shifts and daily rest intervals. The frequency of rest days and the length of the recovery time are both relevant. Workers may benefit from regular (at least fortnightly) recovery periods of at least 48 hours. These are particularly important for shift workers, especially those working nights as shortened or interrupted sleep over a period can result in them spending part of their rest day sleeping.

- Where there is a greater need for night work (e.g. freight and infrastructure maintenance), limiting the number of consecutive nights would mean more switching from nights to days and back (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 34). Controllers of safety critical work should assess the relative pros and cons of such trade-offs and make a judgement on the best overall solution, documenting their reasoning.

7.65 ORR Fatigue Factors for recovery time:

Shift work and shift patterns

7.66 It is the nature of the railway business that some safety critical workers work rotating shifts, and that these may include night work. As described above, workers may have difficulty in adjusting to shiftwork due to the effect of the internal ‘body clock’ (circadian rhythm) regulating sleep and wakefulness, which corresponds to the natural cycle of night and day. The design of shift patterns can greatly impact on a person’s ability to achieve enough sleep.

7.67 Adopt forward rotating shifts rather than backward rotating shifts.

7.68 Current thinking (Driscoll and others, 2007, page 191) suggests that starting a shift later than the previous one (forward rotation) may be less of a problem than starting a shift earlier than the last one (backward rotation). More rapidly (e.g. two days per shift type) or more slowly changing shift patterns (e.g. 21 days per shift) may be preferable to a rotating shift pattern that changes about once a week (ORR, 2006).

7.69 For three-shift systems, better patterns rotate rapidly in a forward direction e.g. MMMAANNRR, MMAAANNRR or MMAANNNRR (where M is a morning shift, A is an afternoon, N is a night shift and R is a rest day), with rest days generally best placed after the sequence of nights, to optimise recovery. To avoid early starts and late finishes and reduce sleep disruption on the morning and afternoon shifts, recommended changeover times are close to 07:00, 15:00 and 23:00 (DERA advice for nuclear installation guidance, 2000).

7.70 For two shift systems, similar considerations about the placement of rest days apply. However, fatigue levels towards the end of the shift are likely to be higher with 12-hour shifts, especially if the work is demanding, requiring closer attention to fatigue controls. So, although 12-hour shifts reduce the number of handovers and journeys to and from work, can be popular with some staff due to increased days off, and have been reported as improving staff morale, this must be balanced against the evidence on increased incident and error rates for longer shifts. To avoid early starts on the day shift, recommended changeover time is at or soon after 07:00 (DERA advice for nuclear installation guidance, 2000).

7.71 Avoid consecutive duties with large variations in start times; ideally avoid variations of more than two hours.

7.72 For safety critical workers who are on call, or whose starting time frequently varies with very little notice given, the uncertainty makes it difficult to plan suitable sleep time and fatigue is more likely as a result. A particular example are drivers on a ‘spare turn’, who can have large variations (up to four hours) in their duty start time. When consecutive duty start-times vary by so much, fatigue is highly likely to be a problem. As far as possible, shift start times and on call duties should be planned to avoid variations of more than two hours. Where this is not possible then additional control measures, such as additional rest breaks within a period of duty, or a shorter shift length, should be considered.

7.73 Employers should make reasonable efforts to accommodate personal preferences as these may stem from an ability to cope with certain shifts.

7.74 People differ in their ability to adapt to and tolerate shift work. For instance, studies of ageing and the ability to cope with shift work have suggested that older workers generally cope well with the demands of early shifts but may experience more difficulties with the night shift – with ageing there is a tendency to become more of a ‘lark’ (waking earlier and most alert in the first part of the day) than an ‘owl’ (waking later and most alert later in the day or evening) (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 pages 21, 36 and Appendix G page 9; Monk 2005).

7.75 ORR Fatigue Factors for shiftwork patterns:

Time of day

7.76 The risk of fatigue-related accidents is well correlated to the time of the day.

7.77 Plan safety critical work to avoid times when alertness is low, i.e. particularly from midnight to 6am, but also from 2pm to 6pm, where practicable.

7.78 An RSSB analysis of SPAD (Signal Passed at Danger) incidents indicated that the risk factor increased between two and three-fold between midnight and 06:00 (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 26). A study of data from 8-hour morning, afternoon and night shifts indicated that the risk of an accident was 28% higher on the night shift and 15% higher on the afternoon shift than on the morning shift (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 40). These time of day effects are largely seen as a product of our circadian rhythms of performance and alertness, with increased crash prevalence during the primary window of circadian low during the late night and early morning hours (02:00 to 06:00) and a lesser peak during the afternoon secondary window of circadian low (Pack and others, 1995; Summala and others, 1999).

7.79 Where not practicable to avoid safety critical work at times of low alertness, consider other control measures or changes to the working environment.

7.80 The main problem in the management of shift work is to cover the night-time hours when alertness is naturally low. People who work in the late night or early morning often feel sleepy and fatigued during their shift. This occurs because their circadian rhythm or internal ‘body clock’ is telling them they should be asleep. If safety critical work cannot be avoided at these times, other control measures can help mitigate the effects of feeling sleepy and improve alertness. Examples of such control measures include planned rest breaks, working in pairs and encouraging workers to stand up and move around. Changes that can be made to the working environment to help include higher levels of lighting and lower ambient temperatures.

Rest breaks

7.81 Breaks enable workers to reduce their fatigue and maintain attention. The length and timing of breaks should be appropriate to the nature of the work and the length of time spent on duty.

7.82 Provide breaks during periods of duty, except where the work provides natural opportunities for relaxation or reduced vigilance.

7.83 Frequent short breaks during a shift help manage fatigue and maintain attention. Research (HSE, 1999) found that during periods of high workload, a fifteen-minute break may overcome reductions in performance due to fatigue, a six-minute break overcame many, but not all performance reductions, and a two-minute break was of some benefit but was considerably less effective. Less demanding tasks are likely to require shorter breaks than more demanding tasks.

7.84 Wherever reasonably practicable, safety critical workers who work at a workstation (e.g. in a driver’s cab or signal control room) should be given the opportunity to spend breaks away from the workstation.

7.85 Schedule breaks in the middle of a shift, where possible, but at a suitable time with respect to the task activities.

7.86 Scheduling breaks at the start or end of a shift reduces any beneficial effects (RSSB, 2010 Research Report T699 page 6). Schedule a break in the middle of a shift or plan regular breaks throughout a shift.

7.87 Provide breaks, as appropriate, that are ten to fifteen minutes long, where possible.

7.88 General advice for tasks which require continuous sustained attention, with no natural breaks in the task and where a lapse in attention can lead to safety implications, is for a 10-to-15-minute break every two hours during the day and every hour during the night. For driving tasks, good practice would be to plan a short break about every three hours.

7.89 An alternative to providing breaks is to rotate workers around different tasks, provided not all tasks require similar sustained attention. However, it is unlikely that the majority of safety critical tasks in the transport system would be of this nature.

7.90 Provide suitable areas for workers to take quality breaks.

7.91 The quality of breaks is important. A food and drink preparation area, a quiet rest area at a suitable temperature and with suitable seating, and the facility to talk to colleagues and to take a walk will all provide a positive environment for a break. Daytime naps between 10 and 20 minutes result in decreases in subjective sleepiness, increases in objective alertness, and improvements in cognitive performance (Hilditch and others, 2017). In the case of safety critical workers on a night shift, the facility to take a short nap during a break can be especially beneficial. Even a short nap of 10 minutes can improve functioning (Flin and others, 2008) but naps of no more than 10 minutes are advisable if safety critical tasks are to be resumed within 20 minutes of waking. This is to avoid any latent fatigue on waking from a nap (‘sleep inertia’). Recognition and management of sleep inertia symptoms in the period immediately after waking is critical to re-establish alertness before undertaking safety-critical tasks (Ruggiero and others, 2014). Sleep inertia is likely to be more severe at night when waking from a nap following extended wakefulness due to the interactions with the body clock and prior sleep/wake patterns (Hilditch and others, 2016).

Summary guidance for work patterns

7.92 A summary of the above guidance is provided below. The guidelines are not proposed as prescriptive limits but are intended to provide a framework to help guide dutyholders in defining their own schemes for controlling fatigue risks; the more a working pattern deviates from the guidelines, the greater the likely need to assess and control the potential risks from fatigue.

Implementing your work patterns

7.93 Once the work patterns have been designed, a number of further measures should be taken to ensure they are successful. Firstly, any technology, systems and arrangements that can be made to keep them in place should be implemented. Staff should be trained and instructed to ensure everyone understands fatigue risks and is competent to carry out their work, for example, roster clerks or managers of safety critical workers. Staff should be supervised to make sure that arrangements are followed, and supervisors should have sufficient knowledge and understanding (see 7.98) of how to spot issues with fatigue with their direct reports. Any issues encountered should be reported to the correct authority and investigated or resolved.

Systems, technologies and arrangements

7.94 Since fatigue increases the likelihood of errors, processes which detect the early stages of fatigue, or which detect or mitigate the effects of fatigue-induced errors should be introduced where reasonably practicable. For many years various ‘hardware’ aids have been used in the rail industry to help detect or mitigate fatigue related errors, including for instance the Driver’s Vigilance Device (DVD), Automatic Warning System (AWS) and Train Protection and Warning System (TPWS), albeit with mixed results due to potential habituation effects. More recently Automatic Train Protection (ATP) Systems including the European Train Control System (ETCS) have been introduced. Manufacturers, leasing companies and operators should consider the potential benefits available of developing and introducing improved hardware aids for detecting the early stages of fatigue, and for detecting and mitigating fatigue-induced errors. Additionally, alertness measuring technologies are becoming more viable and can provide useful insights into how to address fatigue issues. Some of the opportunities and challenges of using technology to help detect and monitor fatigue are outlined by Belenky and others (2003). More recent work by RSSB (2021, Research Report T1193) has reviewed the existing technologies and concluded that whilst the rail industry understanding of technology has advanced significantly, the evidence for their adoption is still developing. It is important not to place excessive reliance on such technologies which could lead to wider organisational fatigue controls being neglected with such technologies supplementing, rather than replace, wider organisational fatigue controls.

7.95 RSSB continue to work closely with the rail industry to explore if and how monitoring technologies can support train drivers to improve safety and wellbeing. More information can be found on the RSSB website, Supporting Drivers: Monitoring Attention and Alertness.

7.96 Error detection and correction processes are not confined to hardware fixes – improvements to ‘people’ processes should also be considered. One example is training staff in Non-Technical Skills (NTS), which can help key staff to avoid, detect and recover from errors, whether caused by fatigue or not, and mitigate their consequences.

7.97 See Further Information for references to RSSB and ORR resources and guidance.

Train, educate and brief staff

7.98 Comprehensive fatigue education and awareness arrangements are an essential foundation for managing and mitigating fatigue risks. Dutyholders should provide their staff with clear and relevant information on risks to health or safety due to fatigue, and on their arrangements for managing fatigue.

7.99 Safety critical workers in particular should be made aware of their role and the requirements on them in meeting the arrangements for managing fatigue. They should be aware of the impact of their activities on the safety of the transport system and the influence that their alertness and fatigue can have on that safety when performing safety critical tasks. Such arrangements would usually include content on the following:

- Basic information on the causes of fatigue, the importance of sleep, and the effects of circadian (daily) rhythms on alertness and performance.

- Awareness of the organisation’s FRMS programme, including fatigue related policies and procedures, and the responsibilities of management and employees.

- Personal assessment of fatigue risk and identifying the early signs of fatigue in themselves (see Figure 1.1) or others. This is especially important for staff responsible for undertaking fitness for duty checks and for those responsible for ensuring staff remain fit for duty throughout their shifts.

- The procedures which staff should follow when they identify or suspect fatigue risk in themselves or others.

- Personal strategies for preventing and managing fatigue risk, covering both work and home / personal life issues. This should include:

- the sleeping environment

- proper nutrition

- the effects of caffeine and other stimulants, alcohol, drugs

- the effect of medications on fatigue

- the role of physical fitness in coping with shift work

- the importance of maintaining social contact with family and friends

- Procedures for reporting adverse incidents which could be fatigue related, and fatigue concerns.

- Other topics related to fatigue management specific to the organisation, such as managing risks from travel time, work-related driving controls (e.g. policy on driving to, at and from work), use of rest facilities, any napping arrangements, expectations for the provision and use of lodgings.

7.100 Refresher briefings in fatigue controls should be provided at appropriate intervals, depending on the degree of fatigue risk in a particular role. Fatigue management should in any case form part of managers’ and supervisors’ day to day conversations with staff, especially with staff in safety critical roles.

7.101 It is vital that staff who devise working patterns receive training in roster design and the implications for fatigue. This should include not only the rostering staff but also any staff or trade union representatives significantly involved in devising or negotiating working patterns. Trade unions and other staff representatives have a role to play in making reasonable efforts to ensure that fatigue risk management good practice is considered by their representatives during negotiations on working patterns and other issues having a bearing on the control of fatigue risks so that negotiated terms and conditions and resulting working patterns do not give rise to excessive fatigue.

Manage and supervise staff working hours

7.102 Once work patterns are in place, arrangements should be made to manage staff working hours, that is, overtime (including exceedances), shift exchange, travel time and on-call duties. This is discussed below. Without proper control, these factors can negate well-designed shift patterns and significantly increase fatigue risk in workers. The arrangements made, including the allocation of responsibilities, roles and functions regarding fatigue management, should be documented in the FRMS.

7.103 In addition, arrangements should be made to ensure the fitness of workers via medical assessments during the selection process and via fitness for duty checks. Both are discussed below.

7.104 Manage overtime:

- Planned work patterns may vary when workers are on call or when unplanned overtime needs to be worked, e.g. because of worker shortages or sickness. Some individuals may be keen to maximise their earnings by working as much overtime as possible, with potentially dangerous consequences in terms of fatigue. Companies are therefore recommended to have an agreed policy and arrangements for authorising and risk assessing overtime to minimise the risks from fatigue. Proposed changes to work patterns should wherever reasonably practicable be risk assessed beforehand to check whether they adequately take account of good fatigue management practices (see paragraphs 7.20 to 7.92 in Implementing your plan including the summary in 7.92). Short-notice changes should be avoided so far as is reasonably practicable. See para 7.105 on limiting exceedances.

- If a fatigue assessment tool, or scheduling software, is used as part of the overtime authorisation decision to estimate likely fatigue risks from changes to planned rosters more easily, its limitations should be appreciated (see Appendix D).

7.105 Manage exceedances:

- Dutyholders should ensure that any standards and limits that have been identified, and set are only exceeded with their prior approval, on an infrequent basis and in exceptional circumstances only. Safety critical workers should be made aware of the standards and limits that apply to the work they are to undertake and the nature of those exceptional circumstances in which the limits can be exceeded with prior approval.

- ‘Infrequent basis and exceptional circumstances’ relate to situations where extended working is necessary to avoid or reduce risks to the health and safety of people on a transport system or significant disruption to services, and it is not reasonably practicable to take alternative steps. Such circumstances would include extreme weather conditions, equipment failure, or an accident or other serious incident. By their nature these circumstances will be unplanned and unforeseeable.

- Dutyholders should have a clear, documented process for deciding whether to authorise exceedances of their limits, and staff able to authorise exceedances should receive training in the process. Before authorising an exceedance, the risks should be assessed to decide whether the fatigue risks are likely to be unacceptable. Exceedance authorisation forms are usually used to guide staff through this risk assessment process, which should require those making authorisation decisions to:

- Consider whether any reasonably practicable alternative options are available (e.g. doing the work at another time with less fatigued staff).

- Identify what reasonably practicable mitigation measures may be taken to address fatigue risk.

- Consider the factors which are likely to affect fatigue risks including for instance: the level of supervision; the frequency and quality of rest periods; the working pattern leading up to the requested exceedance; the opportunity for breaks; time of day; nature of the work including how demanding it is; the working environment including lighting and weather; individual factors such as experience and level of alertness; and travelling time.

- Make a written record of the decision summarising the risks considered and the corresponding fatigue controls and mitigation measures (e.g. an exceedance authorisation form).

- Where the organisation’s standards and limits have been exceeded, the reasons for the exceedance should be identified and suitable measures should be taken to reduce the risks arising from fatigue and to prevent the exceedance reoccurring.

- Where it can be foreseen that the limits are likely to be exceeded more than occasionally, e.g. where hours of work are already close to the limits, controllers of safety critical work should plan accordingly and make any necessary contingency provision to ensure that the limits are not exceeded, except on a very infrequent basis. Planned training or safety briefings for safety critical workers should not be a reason for exceeding the standards or limits. Neither should, for example, the existence of long-standing job vacancies, a block of maintenance work extending over a few days (e.g. plant shut down or blockade working) training delays or planned organisational changes that affect the numbers of safety critical workers. All of these should be foreseeable circumstances. In any case suitable action should be taken.

In exceptional circumstances where extended working is necessary, all reasonable steps should be taken to relieve safety critical workers who have worked in excess of any limits as soon as possible and to ensure that they have sufficient time to be fully rested before their next period of duty.

7.106 Manage shift exchange:

- To prevent staff swapping shifts without a proper assessment of the potential fatigue consequences, companies should have a policy and agreed arrangements for shift exchange, commensurate with the degree of risk. These should, wherever reasonably practicable, involve an assessment of fatigue risk by a nominated manager before any exchange is agreed. The assessment should for instance consider whether the proposed exchange is consistent with relevant company limits and good fatigue management practices in terms of minimum rest periods between shifts, changes between night and day shifts etc (see Designing your work patterns paragraphs 7.20 to 7.92). If the assessment includes use of a fatigue assessment tool, the tool’s limitations should be appreciated. Some recent scheduling software packages which incorporate fatigue tools can produce an almost ‘real time’ estimate of likely fatigue levels, provided the system has been fed up-to-date information on hours actually worked, but these should not be used in isolation - see Appendix D.

7.107 Manage travel time:

- There may be an increasingly important role for technology in easily recording and monitoring working time. Electronic swiping of Sentinel or other personal smartcards to book on and off could help companies assess and control staff fatigue risks in many rail occupations, especially if combined with a requirement to record travel time and the location where staff are sleeping (postcode or town). There are other obvious potential benefits of such smart-card technology, for instance in helping ensure that staff have appropriate, in-date competences.

- Recording and reviewing the start and end times of individuals working periods (e.g. booking on and off) is common in some rail occupations and helpful for gathering information on overtime worked but, at present, it is not done for many supervisory and management roles, where there may be an explicit or implicit expectation that staff work the hours required to ‘get the job done’, sometimes without adequate consideration of possible fatigue risks.

- Accurately recording and then reviewing and monitoring the time spent working and time spent travelling associated with work helps a company honestly assess the demands on their employees and the fatigue these demands are likely to generate. This honest evaluation may reveal significant fatigue risks which are being tolerated by individuals because of the prevailing safety culture, but which could cause incidents with serious consequences for staff, others on the rail network or, if staff drive to / at / from work tired, to themselves and other road users. Fatigue risk assessment tools can help assess likely risks from commute and travel times. See Appendix A on Travel Time for further information.

7.108 Manage on-call arrangements:

- Many rail occupations involve some form of on-call duty, especially supervisory and management roles. Unless carefully managed, on-call work can easily operate outside of otherwise reasonable planned working patterns, especially during periods of disruption, staff shortages, emergencies and so on. Sometimes the company culture leads to on-call work going unrecorded, potentially leading to under-estimation of staffing requirements and elevated fatigue risks. Once again, honesty in recording time spent on-call, especially at times when the individual would otherwise be asleep, helps to properly assess and control fatigue risk.

- At present, for many roles the on-call arrangements involve a system where all supervisory and managerial staff are on-call as a ‘just in case’ measure outside their core working hours. For instance, many daytime staff may remain, officially or unofficially, ‘on-call’ most evenings and weekends. In many cases it would be beneficial to change to a more managed on-call rota system where each individual takes their turn (e.g. one in four, one in seven) in taking all on-call queries for relevant colleagues. This can improve risk control by ensuring that only well-rested individuals manage important calls, therefore reducing staff fatigue and improving well-being by reducing disturbed sleep and improving peace-of-mind (staff can leave their work behind them until their next duty period, rather than anticipating calls whilst they are off duty). If personal knowledge is absolutely essential to resolving an urgent on-call issue (such circumstances may in reality be rare), such an on-call rota system may be less realistic.

7.109 Medical assessment:

- ROGS 2006 Reg 24 states controllers of safety critical work are to ensure that a person under their management, supervision or control who carries out safety critical work, is competent and fit to carry out the work so far as is reasonably practicable. Therefore, organisations employing staff for safety critical work should have a competence management system which incorporates suitable medical assessments during staff selection procedures, and for ensuring ongoing staff fitness for duty. General advice can be found in ORR’s Railway Safety Publication 1 ‘Developing and Maintaining Staff Competence’. Various medical conditions and sleep disorders may increase the risk of an individual feeling sleepy. Research in both the road and rail transport sectors has found that the prevalence of a sleep condition called obstructive sleep apnoea (intermittently stopping breathing during sleep, which disturbs sleep and causes fatigue) is higher than in the general population. RSSB has researched obstructive sleep apnoea (RSSB, 2006 Research Report T299) and has produced useful guidance (RSSB, 2014 GOGN 3655 Issue 2).

- Various screening questionnaires have been developed which can help a competent occupational health practitioner in the initial identification of individuals who could be suffering from undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnoea (see for instance the Berlin Questionnaire and the STOP-BANG Questionnaire, accessible via the websites of the British Snoring and Sleep Apnoea Association and the American Sleep Apnoea Association detailed in Further Information). Screening for such conditions periodically and for instance, after any suspected fatigue related incidents can help reduce risks from staff developing such problems as their career progresses – effective treatments are often available.

7.110 Fitness for duty:

- Companies should have fitness for duty checking arrangements to ensure that staff reporting for safety critical work are not suffering, or likely to suffer during their shift, from fatigue. Controllers of safety critical work should ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, that safety critical workers who report for duty where they are clearly unfit due to fatigue, or who, through the course of their work shift become clearly unfit owing to fatigue, do not undertake, nor continue with, safety critical work (ROGS 2006 Reg 25). Fitness for duty checks should include both objective (e.g. hours of sleep or wakefulness) and subjective measures (e.g. how alert or sleepy people feel). Both are considered below.

- Such arrangements seek to identify any issues which may reduce the individual’s ability to work safely including, not only fatigue, but:

- any drug and alcohol use

- illness or its after-effects

- potential distraction or other psychological effects from any recent incident

- work related or domestic problems

- The system should seek to establish whether the individual has had sufficient sleep in the hours before starting work, such that they should be able to carry out their work safely for the whole of their shift.

- Controllers of safety critical work should not allow workers to undertake safety critical work if they have not had sufficient rest before starting a period of duty. The reason(s) why the safety critical worker is or has become fatigued should be established, so far as is reasonably practicable.

- The system should identify not just whether the individual is fit at the start of the shift but is likely to remain fit until the end of their shift – being awake too long before work greatly increases the risk of fatigue later in the work period. If remote booking-on procedures are used, random face-to-face checks should be carried out sufficiently frequently to provide visual assurance that individuals are in a physically fit state for work. In the event of a safety critical worker being so unfit, appropriate control measures (such as providing sufficient rest) should be applied before the safety critical worker commences or recommences safety critical work.

- In addition, various fatigue question-sets and rating scales are available which may help staff checking fitness for duty (see RSSB, 2022, Fitness for duty and assessing fatigue) but a culture of honesty is important to the success of such an approach. The best example to set for staff working when they are fatigued is to develop an open, ‘just’ culture. In a just culture staff take their responsibilities to obtain sufficient sleep seriously, but feel confident that, if on occasion they feel too fatigued to work safely (e.g. due to a new baby at home keeping them awake), they will not be punished for honestly declaring this so that alternative arrangements can be made.

- Safety critical workers should be made aware of the procedures to be followed if they consider that there are circumstances, such as significant life events or medical conditions, that may cause them to either be, or become so fatigued, that health and safety could be affected. Planning for sufficient spare staffing cover, so far as is reasonably practicable, can also help avoid staff feeling compelled to work even if fatigued, but this relies on staff not abusing the arrangements.